Have you ever wondered how and why jeans were invented? Learn the whole story:

Before there were straight, low-waisted jeans, skinny , selvedge , stretch , flare ou boyfriend Then there was simply jeans. Sailors from Genoa, Italy, were the first to wear this cotton and twill fabric from the city of Nimes, France. These Genoese were called “genes”by the French and were later nicknamed “jeans”by the Americans.

Today’s jeans are made from denim, a heavier cotton canvas fabric in which only the warp (yarns arranged lengthwise) is dyed with indigo dye, leaving the weft (yarns arranged crosswise) white. Although the word denim is a corruption of the French “de Nîmes”, it is very likely that the fabric was first produced in England.

When the United States emancipated itself from the British Empire, the former colonists stopped importing denim from Europe and started producing locally with cotton harvested by slaves in the south of the country, which was then spun, dyed and woven in the north. The Industrial Revolution was strongly driven by the textile market, which practically single-handedly sustained slavery in the country. When the cotton gin mechanized processing in 1783, prices, already subsidized by slave labour, fell dramatically. Cheap goods boosted demand, and a vicious circle ensued. In the period between the invention of the cotton gin and the Civil War, the US slave population increased from 700,000 to a staggering 4 million.

After the Civil War, companies like Carhartt, Eloesser-Heynemann and OshKosh began offering cotton overalls to miners and railroad and factory workers. A Bavarian immigrant named Levi Strauss set up a store in San Francisco, California, where he sold fabrics and uniforms. Jacob Davis, a businessman and tailor from Reno, Nevada, bought denim from Strauss to make pants for workers, and put metal rivets in them to prevent the seams from opening up. Davis sent two samples of his riveted pants to Strauss and together they patented the innovation. Soon after, Davis joined Strauss in San Francisco to oversee production in the new factory. In 1890, Strauss assigned the identification number 501 to his denim pants with copper rivets in the fly. Levi’s 501 jeans were born, and went on to become the best-selling garment in the history of mankind.

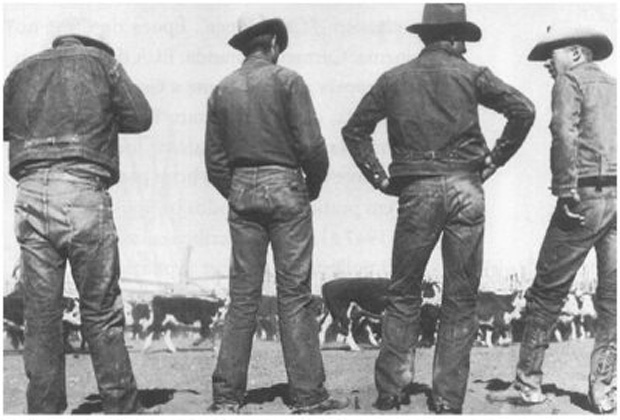

Initially, jeans were worn by proletarians in the west of the USA, but wealthier people in the east also ventured out in search of the vigorous authenticity of the cowboy. In 1928, a reporter from Vogue returned to the eastern United States after a trip to a ranch hotel in Wyoming with a photo of herself that read:“Wearing the unbelievable jeans […] And a smile you can’t find anywhere on Manhattan Island.”In June 1935, the magazine published an article that taught its readers the homemade art of wearing out jeans:“What she does is run down to the local store and ask for a pair of jeans, which she secretly leaves floating overnight in a bathtub full of water –the more times a pair of jeans is washed, the better it gets, especially if it shrinks a little.”Today, a more recent innovation also takes place in the dead of night, and undoubtedly between four walls:intentional rips in specific parts of the jeans.

Back then, jeans were a nostalgic souvenir from the increasingly remote West. By the end of the 1930s, the buffalo was virtually extinct, the vast majority of natives had been placed on reservations and ranchers had fenced off what had once been vast, unobstructed land. Levi’s products were not available east of the Mississippi, making the brand the quintessential Californian. For the rest of the US, it didn’t matter if authentic cowboys wore jeans, as long as movie stars like John Wayne, Will Rogers, Gene Autry and William S. Hart did too.

Workers at Alexander Farm, Arkansas, picking cotton in 1935. Photo courtesy of Ben Shahn/Library of Congress.

Workers at Alexander Farm, Arkansas, picking cotton in 1935. Photo courtesy of Ben Shahn/Library of Congress.

In the southern US, with the end of the lease system, jeans had a different connotation. In 1941, a fashion article in the magazine Life entitled “Doris Lee Offers the Southern Negro,”featured a series of drawings by the artist à la Maira Kalman of African-American women with their bellies out wearing single-front blouses, turbans and colorful skirts. These drawings were juxtaposed with photographs of white women wearing similar outfits. The text read:“[The artist] explains that these coastal black women, more primitive than those from anywhere else, have a flair for color, a ‘strangeness of proportion’, great talent and ingenuity, especially in their adaptations of discarded clothing.”A couple of images included “faded overalls […] readily adapted into capri jeans”. The article suggests that, like the blues, American jeans styles were adapted –or stolen –from African Americans. It took decades for blacks to embrace the denim fashion, as it referred to a brutal history of violence, oppression and exploitation.

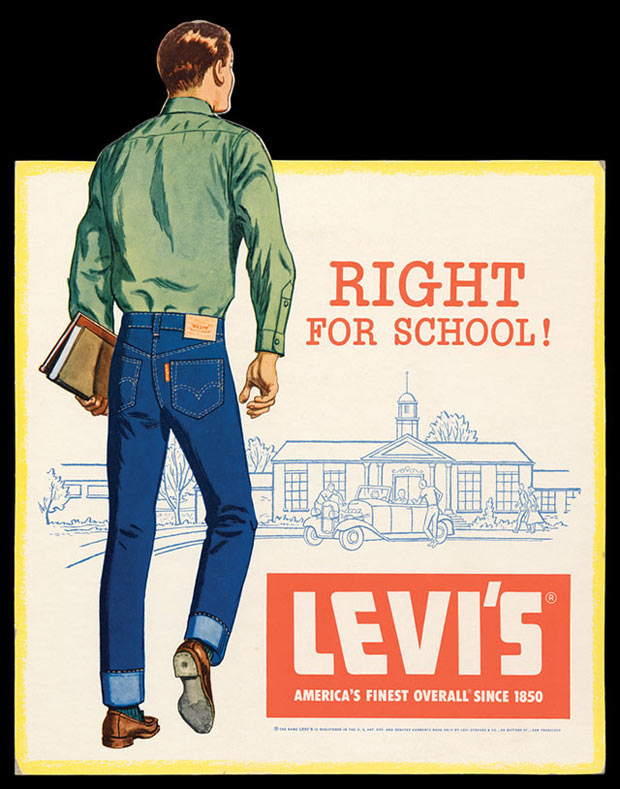

During the Second World War, American soldiers serving abroad wore jeans on their days off, exporting their appeal as a Western style of democracy. From then on, the fascination with jeans only increased around the world. The East German authorities, for example, noticed the prevalence of “cowboy pants”in a workers’revolt in 1953. Jeans represented a similar type of rebellion in the post-war USA. But brands were not ready to associate their products with anti-authoritarian delinquents like Marlon Brando, who wore a 501 in The Wild One . Instead, they saw this semiotic transformation as the disturbing death of the lined-up cowboys of movie posters past. The Wild One After all, it was a riot between biker gangs. The newspapers made a point of mentioning when the thugs were wearing jeans and schools banned the wearing of jeans. Instead of exploiting the bad boy and embrace what could have been an easily executed advertising campaign, denim manufacturers tried to camouflage the situation with slogans like “Jeans:Ideal for School”. They even formed an organization called the Denim Council to promote healthy beauty contests to elect the “queen of jeans”and dress JFK’s first Peace Corps volunteers. But it was all in vain.

At the end of the 1960s, actors like Steve McQueen, Paul Newman and Dennis Hopper hit the screen in films like Indomitable Rebellion e No Destination ;the counterculture was assimilated by the mainstream and teenagers entered the consumer market with great purchasing power. “The fact that mass consumption, with all the standardization it implies, could somehow be reconciled with unbridled individualism was one of the cleverest tricks ever invented by Western civilization,”wrote historian Niall Ferguson in Civilization:The West and the Others , 2011.

Ferguson’s statement could be considered, on an international scale, as a sociological enigma of the Cold War era –as a widely accessible piece of proletarian clothing, jeans were the ultimate symbol of the paradox of consumer culture for the USSR. He sums it up well, “Perhaps the greatest mystery of the entire Cold War is why the Workers’Paradise was unable to produce a decent pair of jeans?”.

When bikers and beatniks adopted jeans, manufacturers tried to camouflage their image by showing well-groomed young men wearing jeans. Photo courtesy of Levi Strauss &Co.

When bikers and beatniks adopted jeans, manufacturers tried to camouflage their image by showing well-groomed young men wearing jeans. Photo courtesy of Levi Strauss &Co.

A Life observed the results of this in 1972. “Sensitive to fashion, Russians can be forgiven for seeing jeans as an international capitalist conspiracy,”published the magazine. A smuggled pair of Levi’s could cost $90 on the Russian black market, and American travelers financed vacations in Europe by selling a few pairs. Soviet officials even coined the term “jeans crimes”to describe “violations of the law instigated by a desire to use any means to obtain articles made of denim”.

In the 1970s, jeans began to feature in the fashion collections of major designers. The fit had to be perfect. American designers such as Ralph Lauren, Oscar de la Renta, Geoffrey Beene and Calvin Klein turned jeans into a status icon and made a lot of money with their garments. Klein, in particular, understood the sexual potential of a firm butt inside tight jeans. In 1976, he adjusted the cut to accentuate the buttocks of the wearer. Three years later, Klein already dominated 20% of the fashion market.

A controversial Calvin Klein advertising campaign from 1980 featured Brooke Shields, then 15, saying “Do you want to know what stands between me and my Calvin?”. Klein quickly turned 25 million dollars into 180 million. That was before denim with stretch flooded the market, so not only were these pants exceptionally high-waisted and tight, they were also thick and inflexible –so tight and rigid that women had to lie down and use tweezers to get the zipper up.

If the sexy fit defined the 1970s and early 1980s, the next phase of denim culture was focused on the finish –acid and bleach washes were used to enhance the garment, as well as stones, scissors and pins. The style may have come from the streets, but designers like Vivienne Westwood and Dolce &Gabbana took punk-inspired denim to the catwalks. In 1988, the new editor-in-chief of Vogue Anna Wintour put a model wearing faded Guess jeans on her first cover.

By the mid-1990s, denim had already been appropriated by designers from major brands. Tom Ford embroidered and filled jeans for Gucci with beads and feathers. Frayed and slightly oversized, they sold for more than $3,000. “The first shipment had already been sold out entirely to order before it even hit the stores,”reported the New York Times . “Winona Ryder, Mariah Carey e Helen Hunt compraram a saia;Gwyneth Paltrow e Cate Blanchett, a calça. As cantoras Lil’ Kim, Janet Jackson e Madonna pediram as duas.”

Diesel was the first brand to manage, in a risky but successful way, to bring faded premium jeans with an Italian design to consumers in the American suburbs. The brand paved the way for bell-bottoms and the “mustache”wash (those faded crease marks that come out of the fly) with $100 labels. Brands such as Seven for All Mankind, Habitual, Citizens of Humanity, Paper Denim &Cloth, True Religion, Chip &Pepper, Earl, Yanük, Frankie B. and many others followed suit and included yarns from stretch to allow for a much lower waist, leaving the panties showing.

Now, in the midst of the Great Recession, we’re coming full circle, with a fairly recent demand for nostalgic “traditional”jeans reminiscent of the miserable industrialism of the Great Depression:workers’shirts and denim overalls in shades of royal blue and straight-cut, functional double-dyed dungarees. Like their forerunners from the 1920s and 1930s, these jeans look rather nostalgic for a country of the past (perhaps with a better fit this time). We’ve entered the Dorothea Lange era of fashion –dresses with speckled wool cardigans, fabulous flannel shirts and sturdy boots –the Depression era from head to toe.

The look is catalogued in magazines such as Free &Easy This is where many of the traditional denim garments mentioned above come from. In the 1970s and 1980s, American machinery perfected cheaper, bulkier production. The Japanese, on the other hand, went in the opposite direction, working with good designers, using old looms and less consistent yarns. The resulting fabrics have the kind of selvedge (worn finish on the edges of the material) fetishized by denim snobs the world over. They wear with much more personality than the jeans of past decades, which are softer and go through more washes. A new generation of bloggers has been obsessively documenting the wear of their jeans, extensively cataloging brands, ages, washes and uses. The phenomenon is reminiscent of the current fashion for producing artisanal drinks aged in barrels.

We have entered the Dorothea Lange era of fashion.

The vast majority of Americans don’t have the money to spend on fancy jeans. Most shop at places like Walmart, where two jeans from the house brand, Faded Glory, can be purchased for around US$22. Adjusting for inflation, that’s the same price as the reporter from Vogue paid for a pair of pants in 1928. Of course, these cheap clothes hide the price that American jobs pay. Cotton Incorporated reported that only about 1% of jeans sold in the US are made in the country. By 2009, most American denim manufacturers had closed their doors and production was transferred to factories in China, Mexico and Bangladesh.

Perhaps the nation of unemployed Americans wearing jeggings is a perverse vision of a dystopian future. Somewhat surprisingly, Glenn Beck spoke out on this issue last year and launched his own line of American-made jeans ($129.99 a piece) via a jingoistic advertising campaign after becoming upset with Levi’s advertisements –he thought they glorified “revolutions and progressivism”. Beck is by no means the first Levi’s customer to confuse his own values with his jeans brand, but regardless of denim nostalgia, the issue is no longer just American.

The American jeans market has been left in the dust;Latin America and Asia are driving the future of denim. So there is a small, healthy denim production chain alive in Los Angeles, and one of Levi’s first suppliers, Cone Denim, still produces in North Carolina, where small-scale manufacturers like Raleigh Denim sell their products. Perhaps one of these operations will be able to grow into an economy of scale, making “Made in USA”accessible to the masses again. Or maybe jeans will go down in history as America’s greatest contribution to the world’s closet.

The oldest known Levi’s 501 jeans, dating from around 1890, were found in a mine in the Mojave Desert. The timeline below illustrates the 501’s transformations from the end of the 20th century to 1978. Photo courtesy of Levi Strauss &Co.

Cone Mill, from North Carolina, has been supplying fabric to Levi’s 501 for almost a century. Today, they also supply material for brands such as Releugh Denim and 3×1 –as well as the 501 made exclusively for J.Crew stores.

Although it may not seem like it, many changes have been made to Levi’s most iconic cut throughout history, including variations in leg width and waist height. Photo courtesy of Levi Strauss &Co.

Source: VICE .